posted 19th April 2022

Here’s a little experiment.

Do you, personally, agree with any of the following policies?

- A law permitting same sex marriage.

- A law forbidding discrimination on grounds of a person’s sex.

- A law forbidding discrimination on grounds of a person’s race.

- Education for all children from 5 - 18, free at the point of use.

- Healthcare for all citizens, free at the point of use.

If the answer to all of the above was ‘yes’, you are firmly in the mainstream of political thinking in the UK in 2022. If the answer to any of the above was ‘no’, you are likely to be seen as an extremist, advocating a radical, or even unthinkable, change of policy. If, however, we had conducted the same experiment in 1922, anyone expressing support for any of the above policies would be seen as proposing something radical, even unthinkable - they would be an extremist.

Societies change, and the beliefs that are considered acceptable change with them. Sometimes this is in the direction of greater tolerance and liberalism; sometimes it is the other way. There is nothing inevitable about either direction of travel, and societies may move in different directions on different issues at the same time. So, for example, over the last twenty years in the UK it has become increasingly normal to regard same sex relationships as equal to heterosexual relationships (a liberal move), while at the same time it has become more acceptable to call for greater restrictions on immigration (a conservative move).

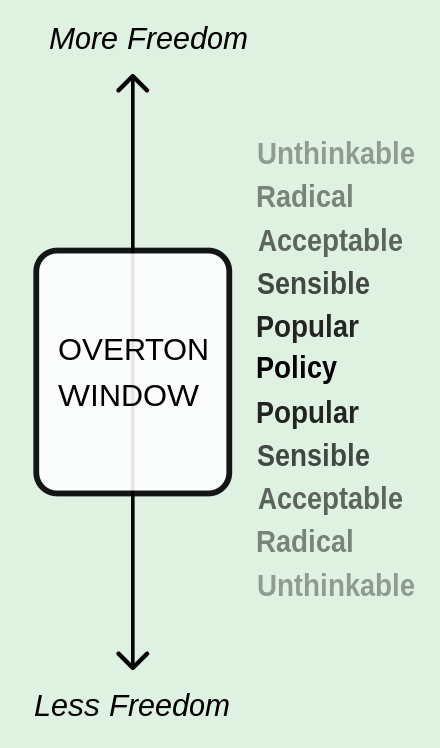

This is where the Overton window comes in useful. The Overton window was invented by the US policy analyst Joseph Overton in the late twentieth century. Overton advised ‘think-tanks’ on how they could change the way that ideas were perceived. His theory was that if you could, through writing, discussion and debate, move an idea from being unthinkable to being popular, it would inevitably become policy, as politicians would have no choice but to respond to the popular mood.

Overton’s colleague Joseph Lehmann developed this theory further after Overton’s death. He proposed six degrees of acceptability for public ideas:

1. Unthinkable

2. Radical

3. Acceptable

4. Sensible

5. Popular

6. Policy

To return to our earlier example, universal healthcare free at the point of use was on the borders between unthinkable and radical a hundred years ago. Since the establishment of the NHS in 1948 it has been policy, and any politician proposing the abolition of the NHS in 2022 would be in the realms of the unthinkable.

Another example from my own experience. When I first became involved in debating in 2000, I set up a debating competition in my school. One of the early debates I set was ‘This house would legalise same sex marriage.’ I well remember the sharp intake of breath when it was announced in assembly; it was a daring move, certainly radical, almost unthinkable, to propose this policy. Even to raise the possibility was to strike a blow for gay rights. Then, in 2013, another debate on the same issue took place, not in my school debating club, but in the House of Commons, as the prelude to a proposed change in the law. Attitudes had changed, and same sex marriage was now seen as somewhere in between sensible and popular, encouraging the then Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron to lead support for the measure. In due course the UK parliament voted in favour of the change, and same sex marriage in the UK became policy. By the time I left my school in 2021 to work full time in debating, it would have been unthinkable to hold a debate on same sex marriage in the school; to even consider that it might not be a good policy would have been seen as a direct attack on the many teachers who were in same sex marriages, and the many students who were out as gay.

How can you use the Overton window in debating? I think it is a useful tool for analysing a motion, and considering how you tackle proposing or opposing it. First decide which of the six categories the motion falls into, and then approach it as below.

Unthinkable

There are some motions which are unthinkable in the sense that they should simply not be debated, either because what they propose is immoral (e.g. compulsory euthanasia for disabled people) or flies in the face of established fact (e.g. ‘This house does not believe in climate change’) or directly attacks members of the school community (e.g. ‘This house would repeal the law on same sex marriage’). Beyond these, there are motions which propose measures which are moral and rational but in the current climate seem unthinkable (e.g. ‘This house would take all land into state ownership’). If you are proposing an unthinkable motion, you have the advantage of surprise, as it is unlikely that the other side will have thought much about the benefits that come with it. Make the most of this advantage by focusing on these benefits, with confidence, as if the measure was just around the corner. If you are opposing an unthinkable motion, be careful not to fall into the trap of simply dismissing the measure as ‘unthinkable’ (to which the response might well be, ‘Well, so were votes for women / the NHS / same sex marriage once.’). Instead, engage with the arguments as given by the proposition, taking them seriously.

Radical

Radical motions make for a harder job for the proposition. They are likely to involve a lot of change - a lot of difference between Now and Then - so you have to assemble your arguments carefully and thoroughly. For the opposition, a successful tactic may be to meet the proposition halfway, by agreeing to move in the same direction as the measure but not as far. For example, a response to ‘This house would restrict all people to one return long haul flight a year’ might be to use a counter-mechanism proposing increasing taxation on international flights, thereby accepting the damage done by air travel and the need to discourage it, but holding back from curtailing air travellers’ liberty.

Acceptable

Now it’s the turn of the opposition to work a little harder. They will have to find reasons why the measure is not, in fact, acceptable. The proposition, on the other hand, have to be careful not to assume that just because something is acceptable it is obvious; they must go back to the reasons it is acceptable.

Sensible

A debater arguing for the proposition for a sensible motion is rather like someone in a long marriage; they have to work a bit harder to keep the novelty and romance alive, and make sure their measure is not taken for granted. The opposition, on the other hand, will need to dig a bit deeper, to get past the obvious assumptions and show why the measure is not in fact as sensible as it looks.

Popular

Just because a measure is popular does not mean it is right. This is the mantra both proposition and opposition must hold on to with a popular motion. The proposition must be very careful not to fall into the fallacy of ‘argument by democratic majority’ (‘Opinion polls show that 73% of people are in favour of x, so therefore we should do it’). The opposition do need to recognise and accept that a measure is popular, but must patiently and thoroughly unpack why it is still wrong. In doing this they must be careful not to be sidetracked into asserting that the majority only support this measure because they have been lied to or, even worse, because they are stupid. (This was the mistake made by many campaigners for a second referendum on Brexit.)

Policy

When a measure is policy, i.e. is currently being implemented, it is likely that the proposition will be calling for reversing or changing that policy (e.g. ‘This house would abolish university tuition fees’). The debate then becomes one about the status quo. The proposition have to argue that the future that will follow from changing the status quo will be better; they will be helped in this task by the fact that almost any measure will have downsides and problems once it is enacted, e.g. they can point to the ways in which tuition fees have discouraged poorer students from applying to university. The opposition will have to argue that the costs of change will be greater than the benefits (e.g. abolishing tuition fees will impoverish universities, restricting what they can offer students), and also to demonstrate the benefits of the status quo (e.g. tuition fees enable universities to offer a wider range of courses). Both sides will be helped by the fact that there will be a much larger evidence base for a policy that is actually in place, and is not purely speculative.