posted 6th May 2025

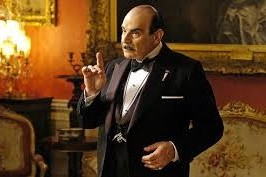

If you’re a fan of Agatha Christie - either her books or the many, many TV and film versions of them - you’ll know all about how red herrings work.

Here’s how they go. Lord Ponsonby of Upper Wallop is found slumped over the desk in his study, an ornamental dagger in his back. By an amazing coincidence, Hercule Poirot just happens to have been staying with him that weekend. He has a look round Lord Ponsonby’s study, and discovers that a locked drawer in the desk in which the notoriously miserly peer kept a large wodge of cash has been forced open and the contents removed. What’s more, Simpson, Lord Ponsonby’s valet, was seen entering the local bookmakers waving a fistful of fivers, which he promptly put on the favourite for the 3.20 at Doncaster, who came in by a length. Easy! Arrest Simpson for the murder.

Not so fast, mon cher ami. Lord Ponsonby was last seen alive by the maid who brought him his coffee at 9 pm. She then discovered him dead when she went back to clear away the cups an hour later. All this time Simpson was in the Ponsonby Arms, buying drinks for half of Upper Wallop with his ill-gotten winnings. The valet is guilty of theft, but not of murder. Poirot goes back to the study and has another look. He discovers an unsigned copy of a revised will disinheriting Lord Ponsonby’s only son. Lord Ponsonby has not spoken to his feckless son for ten years, but the young man just happened to have been in the area and popped in to see his dad on the day of his death to let him know that his latest business venture had failed and he was on the verge of bankruptcy …

Poirot’s suspicions about Simpson were a red herring. That is, something that looks like the solution to a problem, but on closer inspection turns out to be a distraction from the real issue.

What does this have to do with debating?

Here’s how a red herring might operate in a debate. The motion is This house would legalise assisted dying (a proposal which, at the time of writing - May 2025 - is working its way through the British parliament). The proposition points to the funding crisis in the NHS, and suggests that legalising assisted dying will save money because it will remove the need to provide care to people who do not want to go on living. The opposition replies that the proposed new law will in fact increase costs because of the administrative burden which signing off requests for assisted dying will impose on the NHS.

Both sides are guilty of following a red herring. The real issue with assisted dying is not financial, but moral. Which is the higher value? A person’s autonomy and freedom to choose how and when to end their life? Or the sanctity of life itself?

How should you deal with a red herring?

Steer the debate back to the real issue. In this case, the opposition should have replied that costs are irrelevant. Assisted dying is wrong in principle; the NHS should not be doing something as immoral as taking life just to save money. If the opposition raises the cost issue first, the proposition should reply that funding should not be a concern because assisted dying is a compassionate way to save hundreds of people from suffering.

How to avoid red herrings?

Keep pushing back until you get to the heart of the debate. Move past the marginal issues. Ask yourself: if I had to sum up the point of clash in this debate in one sentence, what would it be? For assisted dying, it isn't Is it cheaper to kill terminally ill people or to keep them alive? It's Which is the higher good, personal autonomy or the sanctity of life?

Once you have found the point of clash, keep relentlessly focused on it throughout the debate. If any red herrings appear, steer gently away from them.

Oh, and if you ever become a detective, do look round the crime scene properly before you arrest someone.